From Feb. 17, 2021, NOAA satellites monitored a large plume of dust from the Sahara Desert as it traveled off the west coast of North Africa and across the Atlantic Ocean.

The geostationary GOES-16 (GOES East) satellite keeps constant vigil over the same area, orbiting more than 22,300 miles above the equator, at the same speed the Earth rotates. This view allows us to see the dust in motion.

The polar-orbiting NOAA-20 satellite captured a dramatic image of dust particles blowing out over the Atlantic on Feb. 18. The two Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS) satellites circle the globe from pole to pole 14 times a day, each imaging the entire Earth at least twice daily, from 512 miles above the surface.

Meanwhile, NASA's Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC) on NOAA's Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellite took a wide view of the event, showing the scale of the plume in relation to continents bordering the Atlantic Ocean. DSCOVR is located in an orbit called Lagrange point 1, approximately one million miles away from Earth.

The Saharan Air Layer (SAL) , a mass of dry, dusty air that forms over the Sahara Desert, can transport dust far away from the Sahara throughout the year. While it's more well known for travelling east to west and suppressing tropical storm development during hurricane season, the SAL can also push northward and occasionally blanket Europe with a layer of fine orange dust. Dust within the SAL, which extends about 5,000 to 20,000 feet into the atmosphere, can travel several thousand miles during more active times of the year, bringing minerals that replenish soil nutrients as far away as the Amazonian Rainforest.

NOAA satellites like the geostationary GOES-16 and GOES-17 and the polar-orbiting NOAA-20 and NOAA/NASA Suomi-NPP help forecasters and scientists to continuously monitor the evolution of SAL outbreaks and their effects on the meteorology and climatology of the tropical North Atlantic.

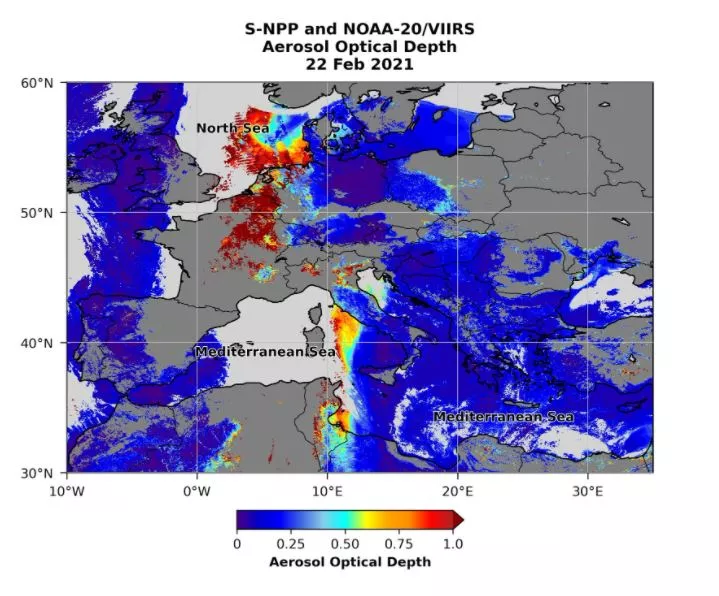

NOAA satellites also track aerosols associated with dust storms. Aerosols are solid and semi-solid particles suspended in the air that have harmful impacts on human health and the environment. They also decrease visibility and lead to unsafe conditions for transportation. Aerosol data from NOAA satellites inform air quality alerts and help air traffic controllers monitor visibility for pilots.

NOAA-20 and Suomi-NPP tracked dust from this event all the way to Europe. This aerosol optical depth data from Feb. 22 shows Saharan dust reaching Europe and the North Sea. The dust is shown as yellow, orange, and red shading, with the thickest dust in dark red.