This article was originally published on September 30, 2020, but has been updated.

October 2020 offered a rare celestial treat—a full Harvest Moon on October 1st and a second full “Blue Moon” on Halloween night. While Blue Moons occur about every two or three years, the last time there was a Blue Moon on October 31st in all U.S. time zones was in 1944.

NOAA’s satellites have a unique relationship with the moon-- Earth’s natural satellite. They use its reflected sunlight, gravitational pull, and orbital position to their advantage--and although not specifically designed to do so, NOAA satellites occasionally catch breathtaking glimpses of the Moon from their perspective in space.

Geostationary Glances

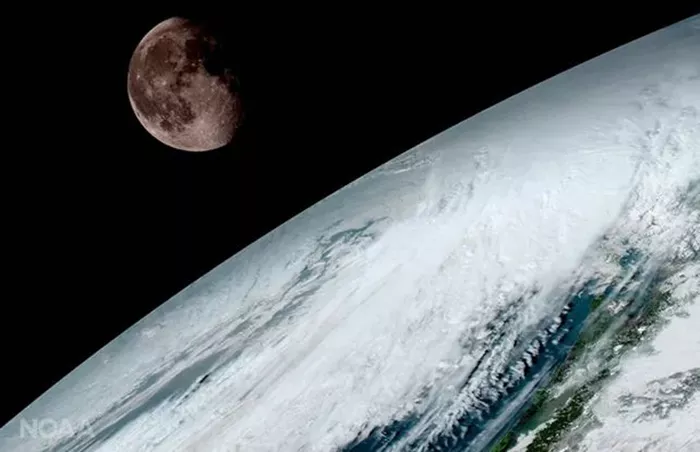

NOAA’s latest generation of Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellites, GOES-R, orbit at 22,300 miles above Earth. In this position, they orbit the Earth’s equator at the same speed the Earth rotates. This keeps both satellites in a fixed position in the sky, and from here, they use their Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) to track the evolution and movement of clouds, weather systems, tropical cyclones, and other environmental phenomena.

This orbit is roughly one-tenth the average distance between the Earth and the Moon, and from this vantage point, the ABI instrument on both GOES East and GOES West regularly captures images of the Moon when it is near Earth’s limb, according to Joel McCorkel, GOES-R Project Scientist for NASA Goddard.

Image from NOAA’s GOES-17 satellite, March 6, 2020

“Besides providing this captivating view, the signal from the Moon provides an independent reference of ABI’s radiometric stability for the reflected solar bands,” McCorkel said. “This signal is not directly used for operational image creation; however, it helps assess the quality and variability of the satellites’ operational calibration.”

Image from NOAA’s GOES-16 satellite, January 15, 2017

Polar Peeks

Orbiting much closer to Earth, roughly 500 miles above the surface, the NOAA Joint Polar Satellite System (JPSS) satellites depend on the Moon to function properly as well. And like GOES, both NOAA-20 and the NOAA-NASA Suomi NPP satellites have instruments that can see the Moon from their perch, according to Changyong Cao, chief of the Satellite Calibration and Data Assimilation Branch at NOAA's Center for Satellite Applications and Research.

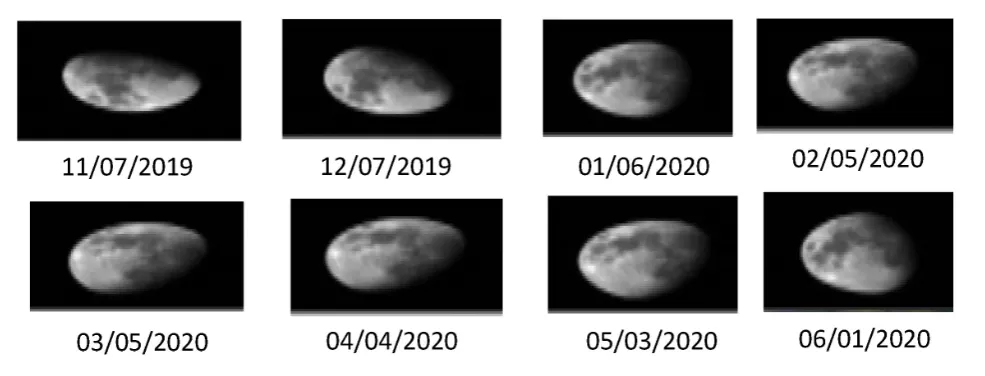

"The JPSS satellite instruments see the Moon from their polar orbit from either their 'space view,' or through dedicated monthly spacecraft roll maneuvers to observe the Moon for accurate calibration," he said. "Specifically, the VIIRS instrument on JPSS satellites heavily relies on monthly lunar calibration."

Images of the Moon from the JPSS satellites’ roll maneuvers, from November 2019-June 2020

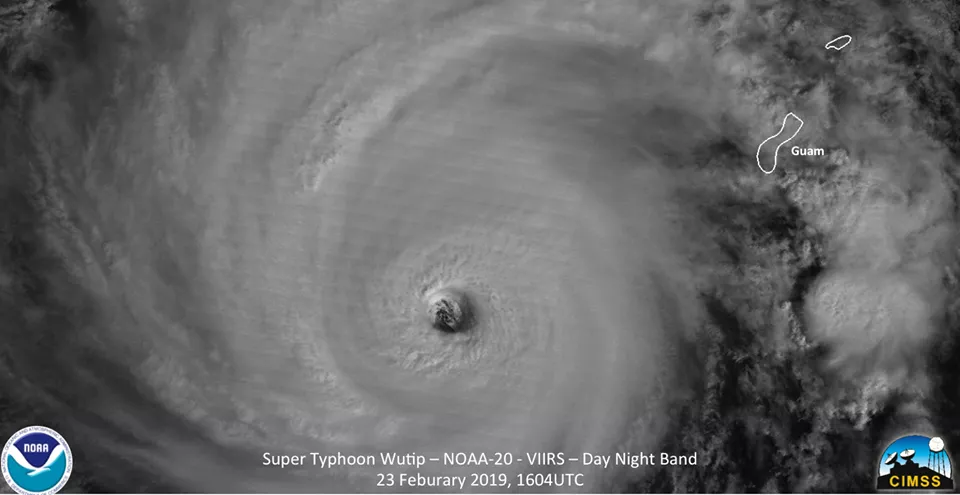

VIIRS, the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite, is one of the critical instruments onboard the JPSS satellites. It has a Day-Night Band (DNB) that is extremely sensitive to light sources. From hundreds of miles up, VIIRS can detect city lights, lightning, fires, and moonlight reflecting off clouds at night. With the Moon as its only light source, the DNB can also detect snow cover, smoke and dust motion, and ice movement in polar regions.

What’s more, a phenomenon called moon glint, where the satellite captures the reflected moonlight off bodies of water, can help pinpoint areas of light winds over water at night. The image below from the DNB shows how the calm water off the Texas coast acts like a mirror and reflects the bright moonlight back at the sensor.

Image from the NOAA/NASA Suomi-NPP satellite’s VIIRS sensor, October 25, 2013

The light visible from the Moon can also help reveal a tropical cyclone’s intensity after the Sun has set. Moonlight helps scientists determine high, cirrus clouds from low-level liquid clouds, enabling them to analyze a storm’s circulation. In this image, moonlight reflected off the clouds of Super Typhoon Wutip revealed mesovortices within the eye of the typhoon, indicating a very strong and well-organized storm.

Image from the NOAA-20 satellite’s VIIRS sensor, February 23, 2019

L1 Looks

NOAA's Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellite is about one million miles away from Earth. In this position--called L1 for Lagrangian point 1, the satellite provides real-time solar wind observations critical for maintaining the accuracy and lead time of NOAA's space weather alerts and forecasts.

Onboard DSCOVR, there is also a NASA-operated camera called the Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC), which points toward our planet and occasionally shows us the celestial dance between the Earth and Moon. About twice a year the camera captures the Moon and Earth together as the orbit of DSCOVR crosses the orbital plane of the Moon.

Time lapse of the Moon’s transit across the Earth’s disk from DSCOVR’s EPIC, July 16, 2015, courtesy NASA

From its position in space, EPIC provides a view of the far side of the Moon--which faces the Sun--that is never directly visible to us here on Earth. It also has captured the Moon’s shadow as it travels across the globe during solar eclipses, like the total solar eclipse that crossed the U.S. in 2017.

Time lapse of the Moon’s shadow passing across the Earth during a total solar eclipse from DSCOVR’s EPIC, March 9, 2016, courtesy NASA

From three very different perspectives, NOAA's satellites don't just provide us with critical environmental data and life-saving weather information, they also let us marvel at our own natural satellite, which has fascinated and inspired humans for millennia.

Find more NOAA resources about the Moon here:

- Science on a Sphere: The Moon

- Science on a Sphere: Moon Transit from DSCOVR

- NOAA Satellites Track the Moon's Shadow During the 2017 Total Solar Eclipse Across America