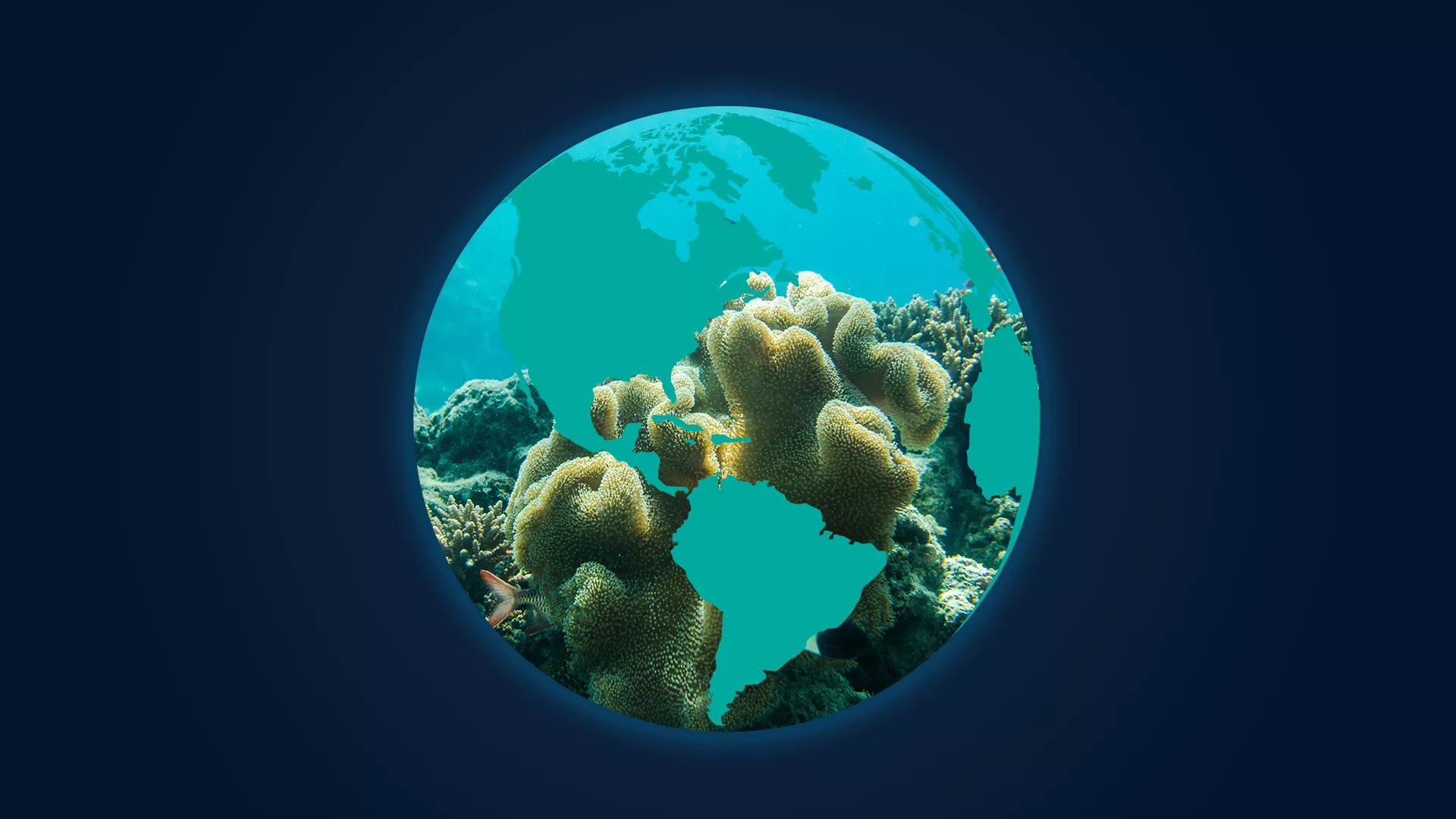

Rain forests may contain more than half the Earth’s plant and animal species, but in terms of diversity, coral reefs are certainly one of the most productive and biodiverse ecosystems in the world. Coral reefs cover an estimated 110,000 square miles of the ocean floor and are home to more than 25 percent of marine species for at least some part of their lives, according to the Coral Reef Alliance.

However, coral reefs aren’t just important for marine life. More than 500 million humans rely on coral reefs for food, coastal protection, and jobs, according to the Reef Resilience Network. Despite the critical role coral reefs play in the day-to-day existence of the human population, many are threatened by climate change.

As part of World Oceans Day, we’re looking at how NOAA’s satellites are monitoring the effects of climate change on coral reefs around the globe.

NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch program uses satellites to monitor ocean temperatures, which, if too high, can lead to coral bleaching. Corals have a symbiotic relationship with the algae that live inside their tissues. While corals provide a home for microscopic algae, it’s not a one-sided relationship. These algae are actually the corals’ primary food source, so they certainly aren’t just getting a free place to stay.

Mark Eakin, the coordinator of Coral Reef Watch, explained that when ocean temperatures get too high, the relationship between coral and algae breaks down.

“It actually causes the algae to be unable to repair themselves quickly enough, and so they start leaching out toxic chemicals, causing the corals to expel their algae into the water,” Eakin explained. “When they do that, it leaves the corals without color, and that’s why it’s called bleaching.”

Can coral survive a bleaching event? If the stress-caused bleaching is not severe, coral has been known to recover. If the algae loss is prolonged and the stress continues, coral eventually dies. (Credit: NOAA’s National Ocean Service )

Bleaching doesn’t kill the coral, but it leaves it injured and without its primary food source. When coral bleaches, it becomes susceptible to disease and might not survive if ocean temperatures don’t cool down quickly, according to Eakin. While injured coral reefs can recover in a matter of weeks by growing new algae, it can take decades for a reef to recover if its corals die.

Using a combination of NOAA and international partners’ satellites, Coral Reef Watch can monitor ocean temperatures and identify areas at risk for coral bleaching. The Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) aboard the GOES-R satellite series and NOAA-20’s Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) provides data on ocean temperatures by looking at the infrared radiation that’s emitted from the ocean.

Eakin explained that this temperature data is compared to the long-term average ocean temperature record or climatology.

“We take those two, the current temperature and the climatology, to generate products focused specifically on corals that allow us to predict when corals are likely to be bleaching,” Eakin said.

Providing this information to natural resource managers and scientists allows them to take action before bleaching occurs. Eakin explained that in 2015, these alerts gave reef managers in Hawaii enough time to rescue rare corals in the wild.

“Those corals they rescued are now being prepared to be placed back in the field, preserving what remains of that species in Hawaii,” he added.

As scientists evaluate new techniques to protect coral reefs, such as creating artificial clouds to deflect solar radiation and keep ocean temperatures from becoming too warm, Eakin said satellite data will be even more valuable.

“Those tools couldn’t be effectively implemented without the ability to predict and monitor heat stress on coral reefs,” he said.

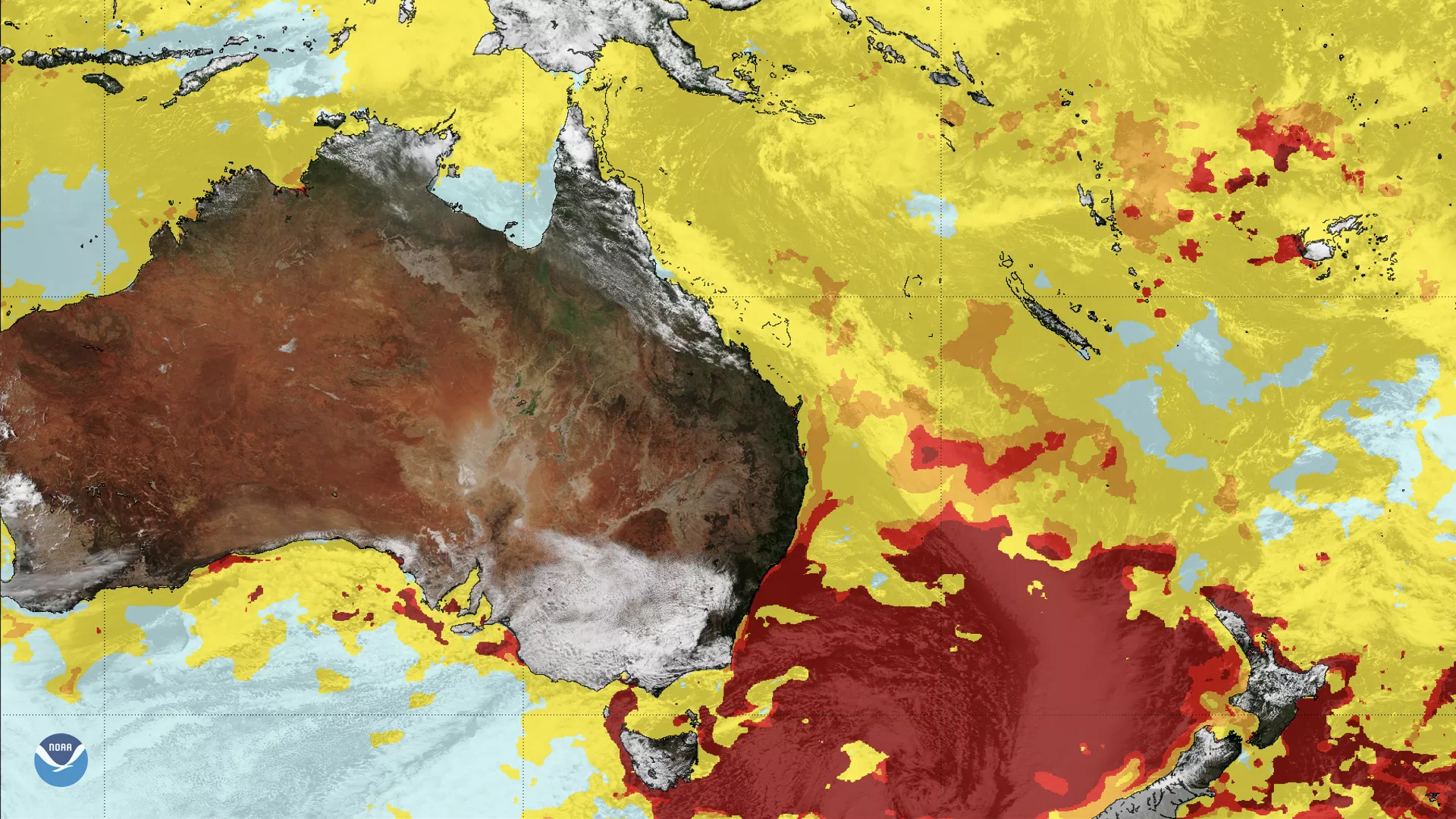

The past five years have been the warmest on record, which has led to an increase in coral bleaching. In fact, mid-2014 to mid-2017 marked the first multi-year global bleaching event on record. The animation below shows the high ocean temperatures that cause coral bleaching moving back and forth between the northern and southern hemispheres during that three-year period.

“So we had corals all around the world bleaching and dying for three years,” Eakin explained. “It didn’t kill all the corals, but it was devastating in some areas such as the Great Barrier Reef suffered back-to-back bleaching in 2016 and 2017.” That bleaching even led to the world’s biggest reef system losing about half of its coral in just two years.

While Australia's Great Barrier Reef is still recovering from back-to-back bleaching events, you can see that the continent is surrounded by coral bleaching alerts in this NOAA-20 image from March 31, 2019. In this imagery, yellow indicates a coral bleaching watch while the red off southeastern Australia indicates a higher level of alert where bleaching and some coral death were happening. You can read about this recent bleaching at Lord Howe Island here.

While it will likely take decades for the Great Barrier Reef to recover from back-to-back bleaching events, there are things we humans can do to protect coral reefs worldwide.

- Educate yourself about coral reefs and the creatures they support. If you don't know where to start, try watching the documentary "Chasing Corals" or head over to the National Ocean Service's website.

- Don't buy or give corals as presents.

- Try to conserve water!

- Volunteer to help out at a local beach or reef cleanup.

Find out more ways to help protect and preserve coral reefs here.