NOAA’s GOES East and GOES West aren’t just part of an esteemed pair of sister satellites, they also belong to an international group of partners in the sky. While GOES East and West keep watch over the Western Hemisphere, their foreign counterparts on the other side of the world image the Eastern Hemisphere. These satellites make up a core geostationary satellite team that provides accurate real-time data to NOAA and the United States.

When GOES-S launches in March of 2018 it will join a fantastic foursome of three other geostationary satellites which together will provide a highly detailed view of weather and environmental events on Earth for NOAA. Together, the GOES satellites, Japan’s Himawari-8 and Europe’s Meteosat-10 are part of an international partnership to monitor complex and changing atmospheric conditions. These four satellites are also part of a larger team. There are other geostationary satellites operated by Europe, China, India and Korea for example that image the Earth and supply essential weather information, and still others that provide backup and supplementary support.

When Weather Goes Global

Why do Americans need to know if there’s a dust storm in Africa? The Earth is one interconnected environmental system, and a low dust storm season in Africa may be the first sign of a developing tropical wave that will become a hurricane in the Atlantic and move toward the East Coast of the United States. Hurricanes are fueled by ocean heat and atmospheric moisture, but dry air associated with massive dust storms like those in the Sahara can help diffuse this development. One of the most critical justifications for global satellite cooperation is to monitor developing weather events. Accurate weather forecasting out to 7 days is available due to shared data access.

Weather forecasts are created by combining elements of temperature, pressure, wind speed and precipitation data with patterns in the atmosphere and characteristics of the ocean and land. The geostationary satellites are positioned high enough above the Earth to see clouds at the top of the atmosphere and the movement of atmospheric moisture on a global scale. The information transmitted to forecasters about water vapor, for example, can be used to find a jet stream or to calculate the amount of moisture that will be associated with a rain or snow storm.

This is how meteorologists are often able to give emergency managers notice of a severe storm with enough time to pre-position resources or evacuate vulnerable populations.

Who are Our Geostationary Partners in the Sky?

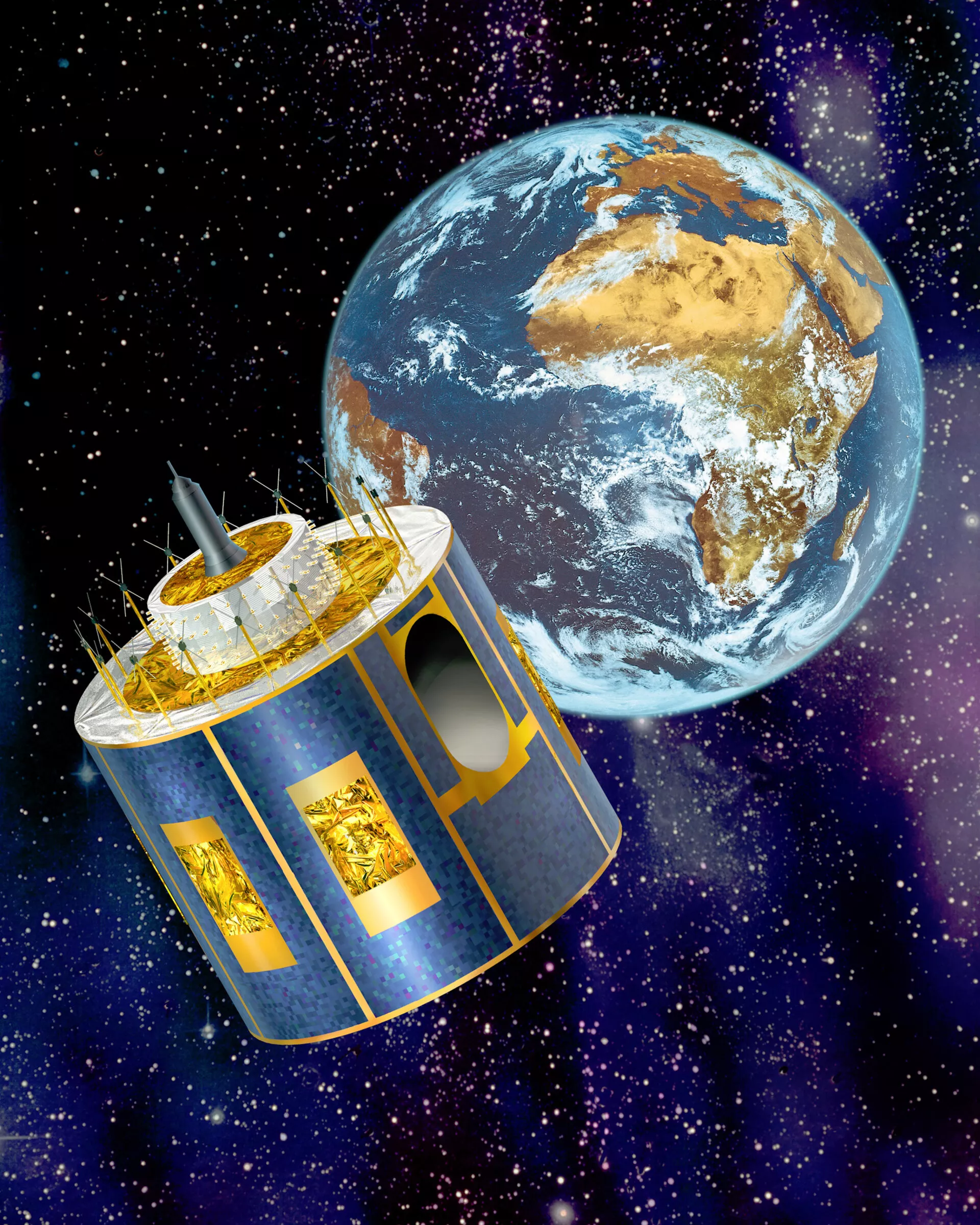

In geostationary orbit at approximately 22,300 miles above the equator, the Meteosat-10 satellite operates over Europe, Africa and the Indian Ocean. Meteosat-10 (launched from the Guiana Space Centre in Kourou in 2012) is the operational geostationary satellite, positioned at 0 degrees and providing full disc imagery every 15 minutes. Meteosat-10 is equipped with the Spinning Enhanced Visible and InfraRed Imager (SEVIRI), which observes the Earth in 12 spectral channels and the Geostationary Earth Radiation Budget (GERB) instrument, a visible-infrared radiometer for monitoring the amount of radiation on Earth. Meteosat-10 is part of a team of satellites operated by EUMETSAT (European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites) which include Meteosat-8 and Meteosat-9.

The Meteosat-10 satellite.

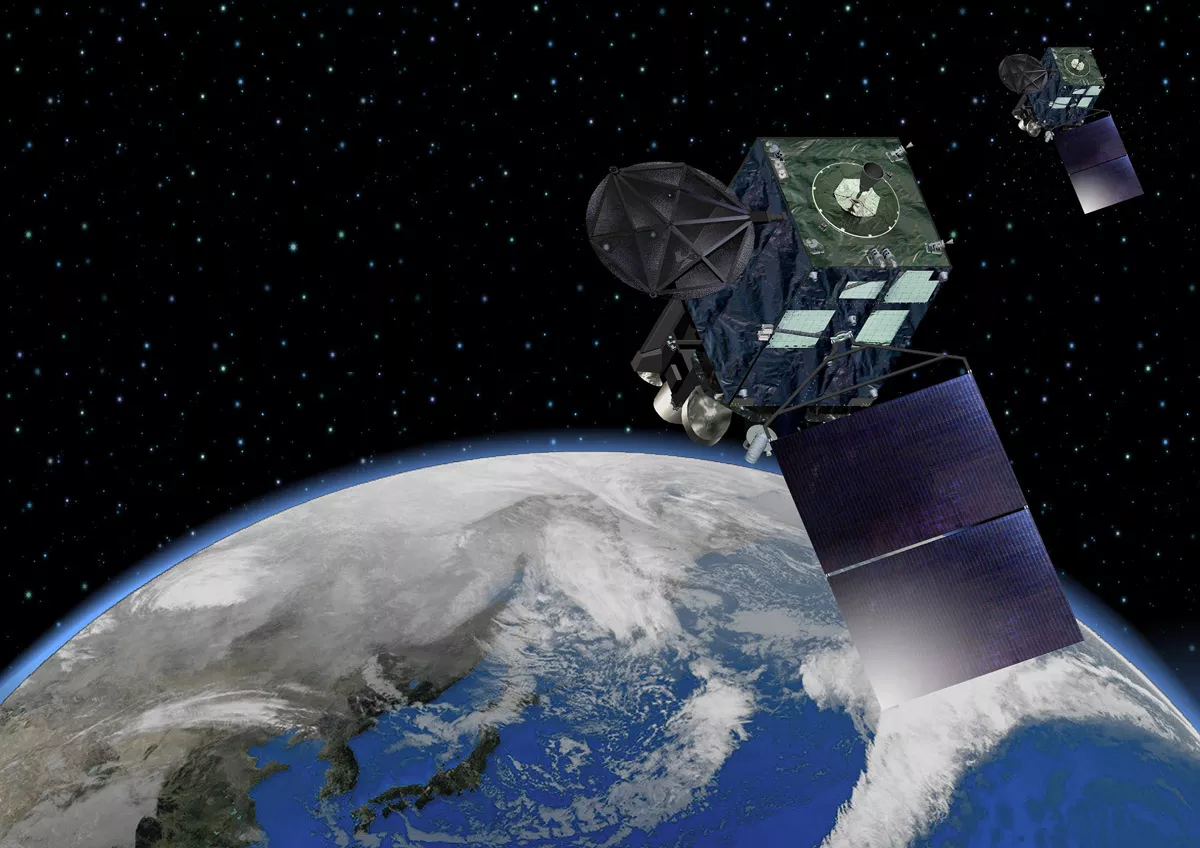

Watching over the Western Pacific, the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) operates the Himawari-8 satellite. Himawari-8’s Advanced Himawari Imager is nearly identical to the GOES-R and GOES-S Advanced Baseline Imager. After Himawari-8 was successfully launched in October 2014 from the Tanegashima Space Center in Kagoshima, Japan it allowed NOAA scientists to access and plan for data they would be receiving from GOES-R before it launched in November 2016. Himawari-8 holds the first 16-channel imager (like the one on NOAA’s GOES satellites) onboard a geostationary satellite and ushered in a new generation of weather satellites.

Himawari-8 satellite.

Partners in Climate

Satellite information used to measure climate is another critical aspect of shared international data. In October 2017, an inventory of more than 900 satellite data records addressing essential climate variables (ECVs) was made available to the global public. This vast data record includes satellite observations of sea surface temperature, land surface temperature, air temperature, ozone, aerosols, precipitation and fire. Geostationary satellites all contribute to this important record - and are able to provide detailed coverage of the Earth.

The GOES Advanced Baseline Imager and Himawari’s Advanced Himawari Imager aid climate monitoring by continuously using cloud data to record the amount of energy that reaches and leaves the planet. The more heat or energy trapped beneath cloud cover, the warmer the planet gets. With the ABI and AHI’s new (and improved) data, climatologists will be able to incorporate three times more spectral information at four times greater resolution into future models.

Learn more about NOAA’s international agreements and partners here!