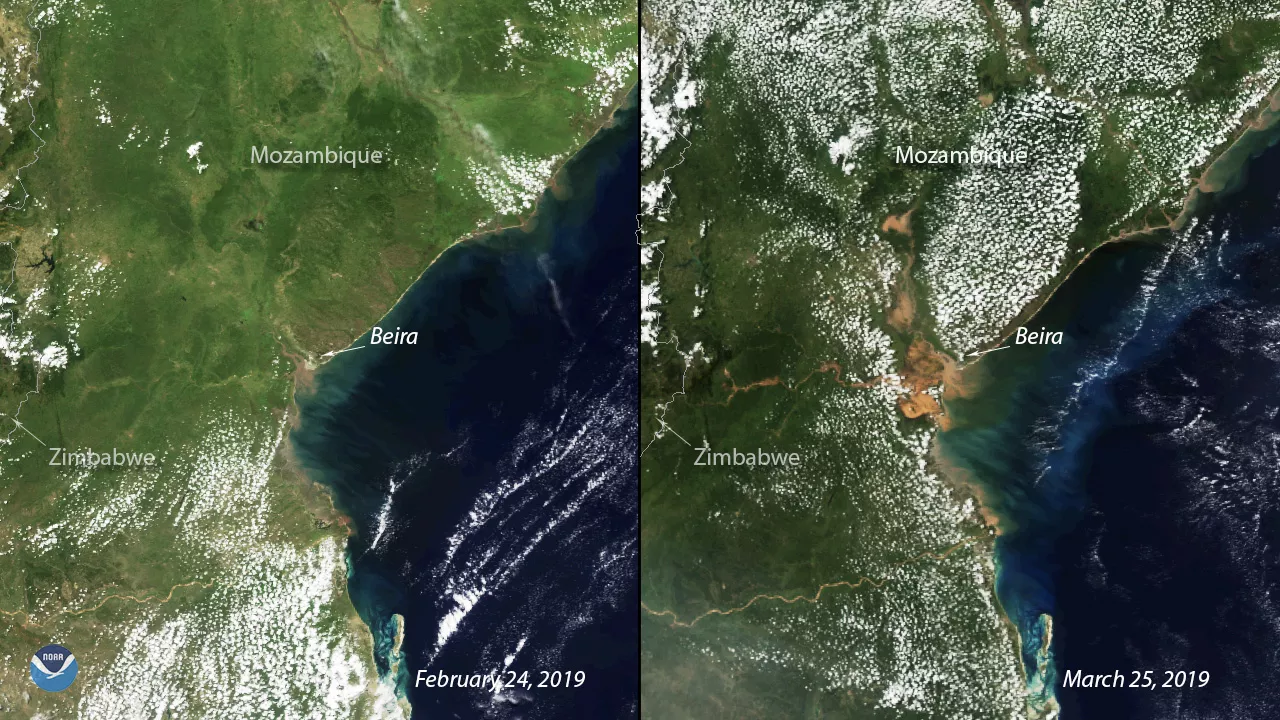

Exactly two weeks after Tropical Cyclone Idai barrelled through Mozambique’s coastal city of Beira, the devastation on the ground remains visible from satellite imagery. These two images from the NOAA-20 polar orbiting satellite show a stark comparison of what the region looked like on Feb. 24, 2019, versus March 25, 2019, nearly two weeks after the Category 2 cyclone hit. Widespread flooding is evident in the coastal communities along the Mozambique Channel and stretches from Pungwe River inland to Lake Urema in Gorongosa National Park.

The devastating storm left more than 400 dead in Mozambique while claiming another 300 lives in Zimbabwe and Malawi, according to the latest report from the United Nations. Much of the area’s infrastructure was destroyed by the 150 mph winds and flooding brought on by Idai, so the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is working with national Red Cross societies in all three countries to help people mark themselves as “safe†and reunite families. The ICRC’s forensic team is also working to locate and identify the dead.

While the floodwaters remain, the World Health Organization (WHO) warns that the biggest threat is now waterborne illnesses like cholera, malaria and typhoid. On Wednesday, officials confirmed several cases of cholera, noting that the WHO is prepared to set up three cholera treatment centers to distribute 900,000 oral vaccines.

The United Nations is calling on the international community to provide $282 million to help the nearly 2 million people affected by Idai. Mozambique is currently ranked third among African nations most exposed to weather-related threats, according to the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery , which works to “reduce vulnerability to disasters in a changing climate.â€

This image was captured by the NOAA-20 satellite's VIIRS instrument, which scans the entire globe twice daily at a 750-meter resolution. The VIIRS sensor provides high-resolution visible and infrared imagery of Earth's atmosphere, land, and oceans, and helps atmospheric scientists monitor severe weather events such as hurricanes and tropical storms.