On March 1, 2018, at 5:02 PM ET, NOAA’s GOES-S satellite blasted off into space and soon took its place as GOES-17, the nation’s newest satellite in NOAA’s most advanced geostationary series. The Atlas V rocket that launched the satellite propelled it into orbit 22,000 miles above Earth. Although the young satellite has already traveled far from home, its journey to become a vital component of the United States’ weather forecasting operations is only just beginning.

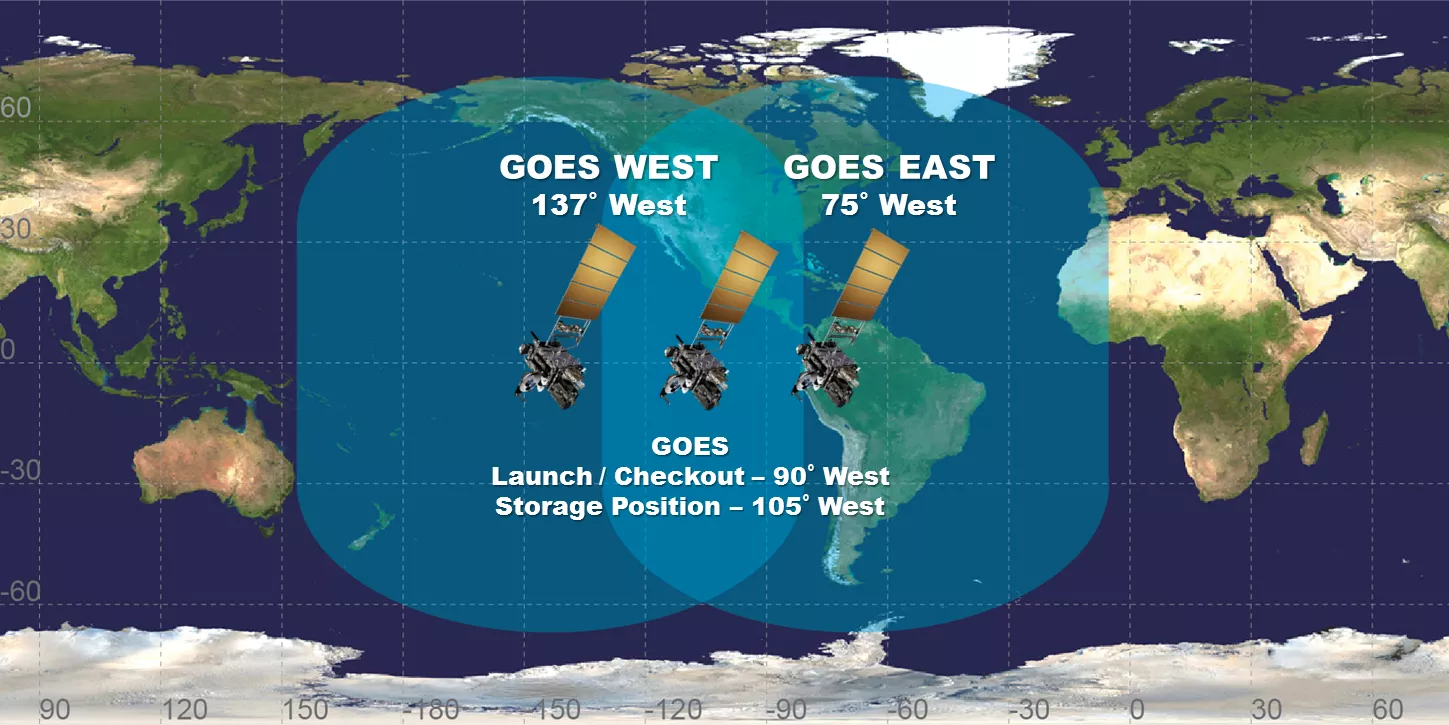

Over the next few months, GOES-17 will undergo checkout and calibration of its instruments and systems. Then it will drift to its operational location at 137 degrees west longitude, where it will capture real-time imagery of the Earth’s Western Hemisphere, from the West Coast of the United States all the way across the Pacific Ocean to New Zealand.

GOES-17 has already completed its first major system checkout - it deployed its solar array approximately three hours after launch, which gave it a power source in space. The solar panels on the satellite recharge the battery-operated power system, enabling the mission team on the ground to control the satellite’s communication abilities and location in space.

Now, the satellite sensors will go through an outgassing process where any chemical residue and water vapor contaminants are released into space before the instruments are activated. Although built in a controlled clean room, even miniscule particles can negatively affect the extremely sensitive satellite sensors. The outgassing process allows one extra ‘cleaning’ before the instruments are turned on.

During the activation phase engineers will check the first data inputs to confirm that they are transmitting as expected, and measuring comparably to current operational satellites, like GOES-16 (GOES East) and GOES-15 (currently GOES West). GOES-17 is equipped with several instruments, including the Advanced Baseline Imager, which will each begin to transmit data back to Earth. Each time we receive initial communication from an instrument, it is referred to as ‘first light.’

The engineers also test the satellite by directing it to perform a series of maneuvers, including rolls (side-to-side movements), yaws (twisting the spacecraft left and right) and pitches (backflips of 180 degrees). These maneuvers give the satellite's engineers and operators a better understanding of the interactions between the instruments and the spacecraft, and how various aspects of the space environment like light and temperature are affecting the sensors.

The final testing phase for GOES-17 will be a detailed inspection and validation of data quality. When GOES-16 underwent this phase, NOAA deployed a team of instrument scientists, ground-based sensors, meteorologists, engineers, drones, and specialized pilots able to fly at high altitudes. They each collected data to compare and calibrate the information being received from the satellite. Now, GOES-16 is an ideal partner satellite to help calibrate GOES-17 data. NOAA’s mission is to ensure that data from our satellites is precise, accurate, and readily available in real time.

Late this year, once these checkouts are complete, GOES-17 will replace GOES-15 as the operational GOES West satellite. Providing faster, more accurate data to the National Weather Service and the public in high definition, GOES-17 will be a game changer to weather forecasting in the western U.S. Millions of people in the United States and around the globe will rely on this satellite for accurate, advanced weather information.