Your cell phone isn't the only device that relies on the radio frequency (RF) spectrum. Buoys, satellites, weather stations, ships, and aircraft all require reliable frequencies to deliver timely weather warnings to you. But there’s a problem: Spectrum is a finite physical resource, and there is only so much of it to go around.

This chart shows United States radio spectrum frequency allocations as of 2011. Click here to see a larger version and explore the busy radio spectrum. Credit: Department of Commerce

Every day, millions of people around the world tap into a vast network of invisible airwaves, known as the radio frequency (RF) spectrum. Used to transmit bits of data from one point to another, nearly every wireless activity uses them. When you answer your cell phone, listen to the radio, stream music, or wirelessly surf the internet, your device is operating on the RF spectrum. Odds are that you are connecting to frequencies right now.

But there’s a problem. Spectrum is a finite physical resource, and there is only so much of it to go around.Imagine the spectrum as a wide open space between two cities (or devices). To transfer goods and information back and forth, roads (or frequencies) are constructed to mitigate head on collisions and chaos.

Our phones and computers aren’t the only things relying on these invisible information highways, however. Behind the scenes is a crucial infrastructure of buoys, satellites, weather stations, ships, and aircraft that all require reliable frequencies to deliver timely weather warnings to you.

Access to RF spectrum is vital to NOAA’s mission. Data transmission over spectrum is critical to nearly all facets of the environmental information we gather. Every NOAA satellite currently in orbit uses some portion of the RF spectrum to communicate with the ground or other satellites.

Twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, our satellites use a specially designated portion of the spectrum to beam back their vital observations. These observations are used to create accurate daily weather forecasts as well as monitor and predict dangerous weather phenomena such as tornadoes, hurricanes, flash floods, volcanic eruptions, and fast moving wildfire.

As the commercial demand for spectrum grows, frequencies currently used for satellite transmission are being proposed for reallocation to companies and other private entities. This can lead to serious problems when more powerful signals from commercial satellites interfere with the less powerful meteorological satellite signals. When this happens, it becomes very difficult to receive a complete satellite signal, risking the loss of crucial satellite data.

Growing Demand Puts the Squeeze on Spectrum

In 2010, President Obama released a Presidential Memorandum titled Unleashing the Wireless Broadband Revolution in which he urged the regulating agencies, departments, and offices of the U.S. government to collaborate to make more efficient use of the available spectrum. To answer the call, NOAA redesigned and consolidated the GOES-R satellites and ground system to free up 15MHz (1695-1710 MHz). These 15MHz were then auctioned off to the mobile telecommunications industry.

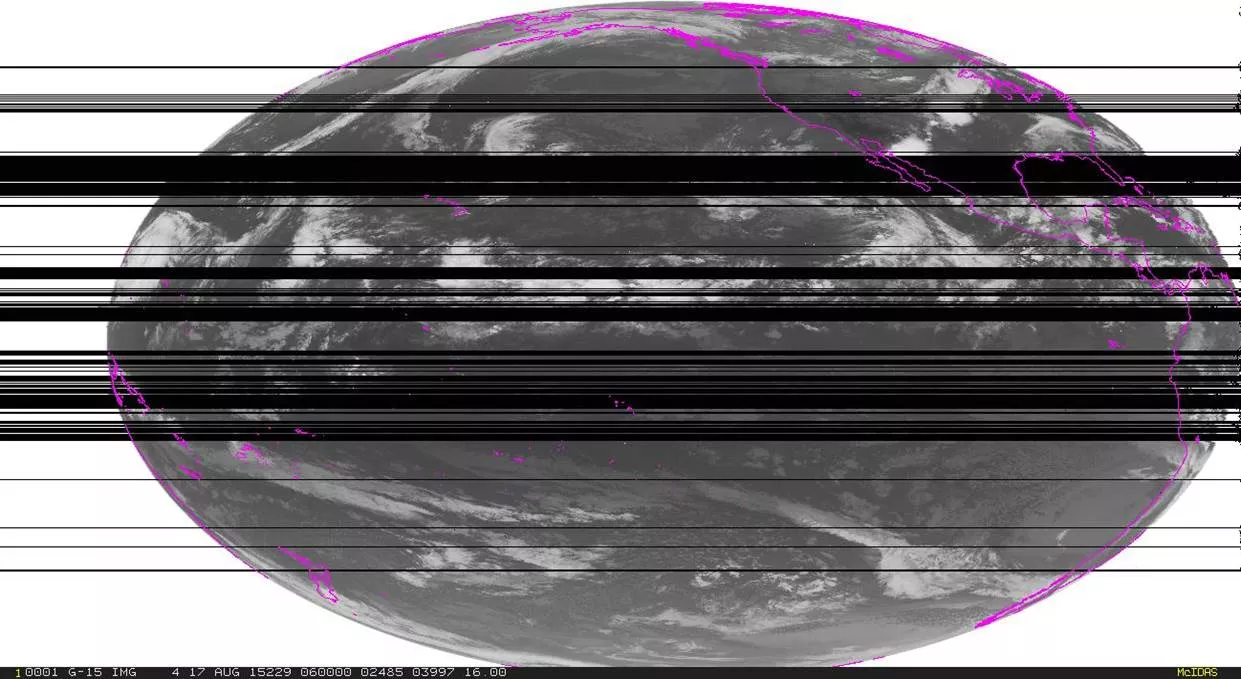

This image was taken on August 17, 2015. The black areas in the image are areas in which weather observations have been lost due to spectrum interference during the testing of the 1675 to 1680 MHz. Credit: NOAA

Now the frequencies 1675 to 1680 MHz, currently used by NOAA, are being considered for auction. Countries around the world use this band for meteorological satellite space to Earth service, and it is used, and will be used, by the existing and future GOES constellations. The loss of these frequencies would affect both our ability to receive data and share it with our users.

We have already experienced interference from test transmissions on these frequencies.Data interference results in the loss of images, including those required to track hurricanes and to monitor the rapid development of severe storms that may develop into destructive tornados.

In addition to disrupting the downloading of satellite data, we expect that the loss of the 1675-1680 MHz band would also interfere with our ability to receive and transmit data from approximately 27,000 terrestrial and remote systems, such as seismic stations, stream gauges, tsunami buoys, and weather stations.

The problem isn't NOAA's alone. By impacting NOAA’s ability to provide real-time environmental observations, radio frequency interference will affect millions of users across the nation.

Before auctioning any additional meteorological spectrum, evaluation and testing is needed to ensure there is no impact to NOAA’s mission to support a weather-ready nation.