When researchers from the Norwegian Polar Institute and the Norwegian Institute for Nature Research (NINA) trapped a young female Arctic fox near her den in Krossfjorden, Svalbard, on July 29, 2017, they were hoping she could offer a bit of insight into the spatial ecology of Arctic foxes. Researchers wanted to know how the animals use their environment in terms of hunting and protecting their territory during different seasons, so they outfitted the coastal or blue fox with a satellite collar and released her back into the wild. Little did the scientists know, less than a year later this fox would traverse barren polar environments, traveling more than 2,700 miles to a remote part of Canada.

Lead researcher Eva Fuglei, in collaboration with Arnaud Tarroux, tracked the fox’s epic intercontinental journey using the Argos Data Collection System (DCS) which is operated under a joint agreement between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the French Space Agency, Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES). So as this fox was going about its daily life, its satellite collar was sending signals at a frequency of approximately 401.65 MHz during three-hour periods every day to different polar-orbiting satellites circling the Earth. Since the late 1970s, polar-orbiting satellites operated by NOAA have carried Argos instruments that are always “listening” for signals from these transmitters. The “messages” are then stored onboard the satellite until it passes over a ground station, explained Scott Rogerson, the Argos Data Collection System Program Manager for NOAA.

Fuglei explained that they chose to use Argos because although GPS collars could provide a more detailed look at the fox’s journey, it would be far too heavy. Argos collars are a lightweight, rugged, long-lasting option for tracking wildlife in near-real-time because the collars are in contact with satellites every day.

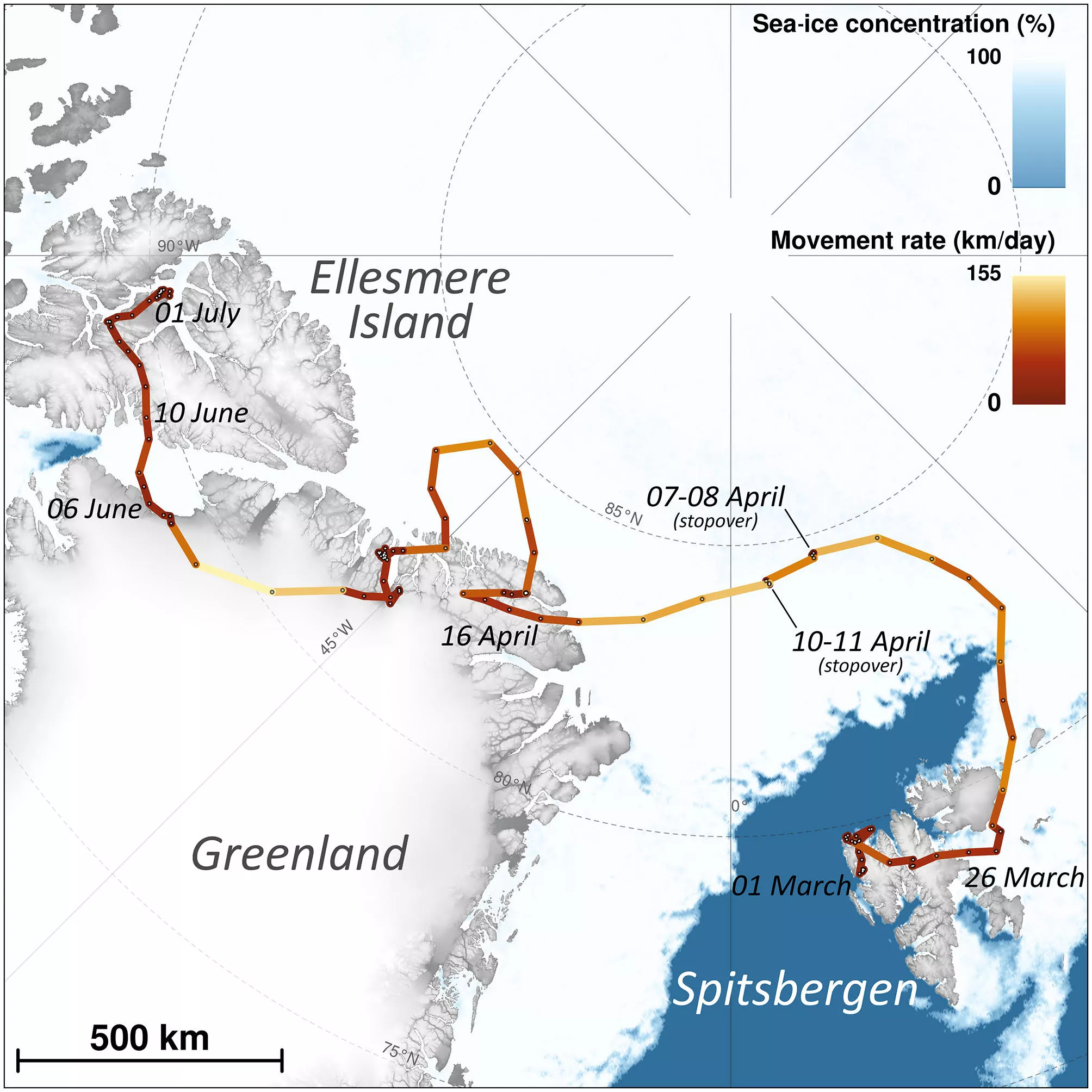

Using the satellite data, Fuglei and Tarroux plotted the fox’s journey from March 1, 2018, to July 1, 2018. The Svalbard fox stayed along the coastline of western Spitsbergen from the time she was outfitted with a satellite transmitter on July 29, 2017, until approximately March 1, 2018, according to the study. The first leg of the fox’s journey, which researchers suggest could have been triggered by food shortages, began shortly after.

“She first moved to the northeast of Spitsbergen and reached the ice-free shore on March 11, 2018,” according to the study. “She then changed course and headed west, reaching the shore, where she again met open water on March 16, 2018.”

After reaching open water twice, the Svalbard fox headed southeast and crossed the northern part of Spitsbergen, where she finally encountered the sea ice that would serve as a gateway to Canada as she ventured north. The fox traveled an average of 29 miles per day, reaching Ellesmere Island in just 76 days.

“This is, to our knowledge, the fastest movement rate ever recorded for this species, 1.4 times faster than the maximum rate recorded in an adult male Arctic fox in Alaska …” researchers noted.

Researchers added that the fox picked up her pace over the Greenland ice sheet, which could be due to a lack of foraging opportunities. The Svalbard fox stopped several times over land, but only stopped for two days while venturing across the sea ice, which researchers said could indicate that she encountered bad weather, physical barriers or food. Of the more than 50 Svalbard Arctic foxes researchers tracked, only one completed such a long journey so far. There are a few isolated Arctic fox populations, and as Fuglei explained, genetic studies indicate that this species occasionally crosses the polar ice pack. However, as sea-ice extent in the Arctic declines, future populations may no longer be able to make this intercontinental trek.

“This may imply that Arctic fox populations in the future may exist as isolated populations on Arctic islands like Iceland, Greenland, Svalbard, Wrangel Island, etc.,” she added.

During the next decade, the Argos network will expand to give researchers even better access to near-real-time data like Fuglei and Tarroux used in this study.

“As we launch more instruments over the next few years, and in particular as the French Space Agency expands to add 25 nanosats to the Argos space segment by 2022, we expect to see much greater use of Argos compared to what we’ve seen for the last decade,” Rogerson said.

Additionally, the Indian Space Research Organisation, NOAA and the European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites also plan to add a new generation of Argos instruments to the mix during the next five years. As the program expands, Rogerson said he hopes the success of this study will inspire others to explore how using Argos can benefit their research.